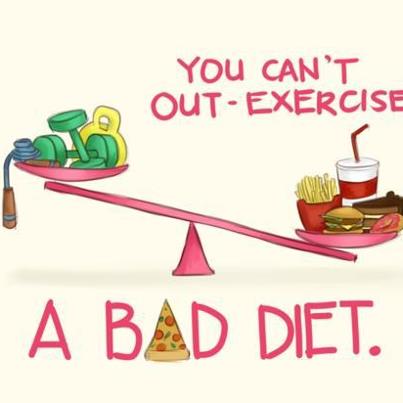

Before we begin discussing exercise and weight loss, let us first make clear that exercise, whether through strenuous running or light walking, produces many positive effects. These include a lower risk for many diseases, improved mental health and cognitive ability, alleviation of many chronic pains and improved utilisation of oxygen by the cells. However exercise has long been considered an integral component of weight management, but available evidence suggests that exercise alone is not an effective way to lose weight.

How we respond to diet and exercise is determined by our metabolism and, understanding this can lead to greater progress and long-term health improvements.

The following article explores the reasons behind why some people slog it out in the gym day in day out yet get zero results [1].

Calories used during exercise

Most of the calories we use each day, fuels the vital functions of the body and only around 20-30% of our total energy is available for exercise. So changing our diet will generally have a significantly greater impact on weight than exercise.

The truth is that you don’t burn loads of calories during exercise, unless you are training like an elite athlete. Perhaps 300 calories during a half-hour, intense session, if that. This calorie “deficit” is almost immediately wiped out by a couple of beers or a crunchy bar.

It is also very common for people to overestimate how many calories were burned during exercise, which leads to more calorie dense food being eaten after, and a gradual weight gain.

Take away – Exercise only represents 20-30% of total energy expenditure.

Hormones and Homeostasis

For those with obesity, insulin resistance and the physically untrained high intensity exercise actually poses a stress on the body. In fact moderate to high intensity exercise provokes increases in circulating cortisol levels [2] which hinders fat burning [3].

Our body strives for a state of homeostasis (balance). When we reduce energy input (food) and increase energy expenditure (exercise) the body is in negative energy balance. When this occurs various physiological mechanisms including a reduction in resting metabolic rate take place in order for the body to maintain weight [4].

Take away – To lose weight and improve body composition you must be burning FAT.

Compensation

Exercise has been known to stimulate hunger [5, 6]. There are several ways in which energy intake could increase in response to exercise. These include increased frequency of eating (snacking), increased meal size, and increased energy density of food [4]. Moreover, if we struggle to use stored fat for energy, we will have to rely purely on our glycogen (the storage form of carbohydrate) stores. When these deplete through exercise we get hungry and this can also lead to compensatory eating [7]. Lets face it we also instinctively want to reward ourselves for the effort we just put in!

Recently, the importance of the contribution of non-exercise energy expenditure has been highlighted. After exercise individuals are likely to compensate by becoming less active and decreasing their non-exercise activity thermogenesis (fidgeting, postural control). This is likely due to neurological and psychological processes [4]. They feel able to justify taking the elevator instead of the stairs after having already done their workout for the day.

Take away – We like to reward ourselves, often by doing the things that make our weight loss journey harder!

Summary

As a society we are doing more exercise than ever, with more gym memberships and organised physical activity, but we are also more overweight than ever. Due to the reasons mentioned above low intensity exercise can actually be more effective in weight loss when working with obese and untrained populations, not high intensity exercise as once thought. In contrast, regular exercise appears crucial in the prevention of weight gain and successful maintenance of weight loss.

Metabolic testing may provide greater information that will help us determine how much and what type of exercise will support rather than hinder our weight loss efforts. This information can be used to determine which foods will support increased fat utilisation and which type of exercise is most appropriate.

References

[1] Bensimhon D.R., Kraus W.E., & Donahue M.P. (2006). Obesity and physical activity: a review. American Heart Journal, 151(3), 598-603.

[2] Hill E.E., Zack E., Battaglini C., Viru M., Viru A., & Hackney A.C. (2008). Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 31(7), 587-591.

[3] Ottosson M., Lönnroth P., Björntorp P., & Edén S. (2000). Effects of cortisol and growth hormone on lipolysis in human adipose tissue. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 85(2), 799-803.

[4] King N.A., Caudwell P., Hopkins M., Byrne N.M., Colley R., Hills A.P., et al. (2007). Metabolic and behavioral compensatory responses to exercise interventions: barriers to weight loss. Obesity, 15(6), 1373-1383.

[5] Hagobian T.A., Sharoff C.G., Stephens B.R., Wade G.N., Silva J.E., Chipkin S.R., et al. (2009). Effects of exercise on energy-regulating hormones and appetite in men and women. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 296(2), 233-242.

[6] King N.A., Hopkins M., Caudwell P., Stubbs R.J., & Blundell J.E. (2008). Individual variability following 12 weeks of supervised exercise: identification and characterization of compensation for exercise-induced weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 32(1), 177-184.

[7] Hopkins M., Jeukendrup A., King N.A., Blundell J.E. (2011). The relationship between substrate metabolism, exercise and appetite control: does glycogen availability influence the motivation to eat, energy intake or food choice? Sports Med, 41(6):507-21.1